Once he said he would do ‘whatever it takes’ to save the euro. Then he had a go at leading that economic basket case called Italy.

Now, arch technocrat Mario Draghi pulls no punches in his 328 page report The Future Of European Competitiveness. If you are skilled in interpreting the euphemistic nuances of the political class, you can easily translate that into its real meaning – Europe has no chance of remaining competitive unless things change drastically.

A leopard can only change so many spots in a decade, but at least his latest calls for more government intervention focus on investment and innovation. There’s even some realism about the mismatch between politically imposed deadlines and the current status of green technology:

“Since around 2010, patenting in low-carbon innovation has slowed down and the current level of green innovation will not be sufficient to meet the EU’s 2050 net-zero emissions objectives. Relevant decarbonisation solutions (e.g. green hydrogen, carbon capture and alternative fuels for aviation and maritime transport) are still very expensive, making them unaffordable for widescale deployment.”

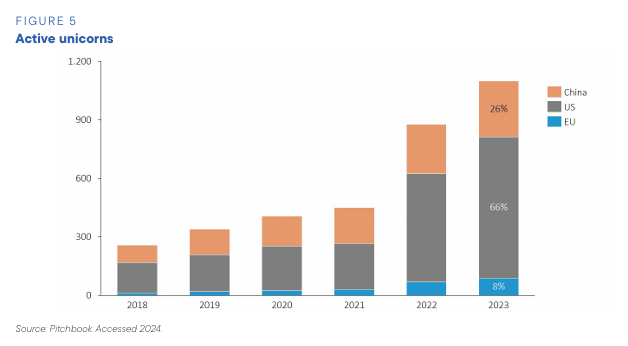

While not specifically blaming the EU’s ever increasing burden of regulation and red tape, Draghi recognises that Europe is failing to produce fast growth technology companies. While the number of startups in Europe is similar to America, the EU’s ability to stifle growth is shown in glorious technicolour when you look at the number of active unicorns compared to America and China:

He points out that the EU has been a leader in advanced materials and manufacturing, the automotive sector (surely a historic perspective in the 2020s?) and biotechnology. But it is critically behind America and China in digital technologies like AI, cyber security and blockchain.

In a more dynamic business environment like America, the past twenty years have seen significant changes in digital leadership. In contrast, the top 3 spenders on R&D in the EU have been in the good old automotive sector. A clear sign that Europe is still fighting the last war:

“In the early 2000s, the top three US companies spanned the automobile and pharmaceutical industries. By the 2010s, they had shifted to the software and hardware sectors; and in the 2020s, the top-three companies included Alphabet and Meta, global leaders in the digital sector. This dynamic business evolution has been notably absent in the EU.”

As well as a plea to streamline EU processes and simplify conflicting laws, he urges the creation of ‘EU innovation hubs’ to help countries to define sandboxes and promote their use by offering centralised information to EU businesses.

The wake-up call comes not a moment too soon. It’s nearly ten years since I brought Harry Dent to the UK to talk about Europe’s demographic cliff. Draghi predicts that the EU’s ageing workforce means that, unless there are major increases in productivity, its economy will be no bigger in 2050 than it is today.

Way back in 1990 when there were just a dozen members of the EU, their combined GDP represented 26.5% of the world’s economy. Membership may have more than doubled to 27 (even allowing for a certain country’s exit), but that share of the global pie has fallen to just 16.1%. In 1995 Europe’s productivity was just 5% behind America’s. Today it lags by 20% and the gap is widening.

One of the few positive elements of Draghi’s report relates to the space sector, where Europe has a strong position but one that has come under threat in recent years. :

“Overall, the European space industry has remained competitive during the past decades. This is noteworthy especially considering that the share of public funding (i.e. the institutional market to which European space companies had access) has been considerably lower compared to that of its main competitors. The EU’s space industry is a net contributor to Europe’s trade balance, exporting globally complete satellite systems, launch services, equipment and subsystems.”

However:

“The EU has lost its leading market position in commercial launchers (Ariane 4-5) and geostationary satellites. As a result, it had to rely temporarily on the US’ Space X rockets to launch satellites for its strategic programme Galileo. Similarly, Starlink’s success is disrupting European telecom operators and manufacturers. Today, whilst retaining technical competitiveness in the space segments of Earth Observation, navigation and exploration, the EU lags behind the US in rocket propulsion, mega-constellations for telecom and satellite receivers and applications (a market much larger than the other space segments). The EU is also highly dependent on imports of high-end electronic components (semiconductors) and detectors.”

The story is not so positive in the defence sector, where the pax Americana has led to a gradual decline in spending over the last fifty years. The average across the EU is still below 2% of GDP, albeit there has been an uptick since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. If everyone met the current rather modest target there would be a €60 billion increase in defence spending. But that’s only a fraction of the additional €500 billion of defence spending the European Commission estimates is required in the next decade.

It’s an impressive report in its scope and specificity. Its author’s pedigree as a Eurocrat is unrivalled. But will anyone listen? Will his recommendations be filed under ‘too difficult’?

The scale of investment needed to reverse the slow decline is mind boggling. How likely are member states to find €800 billion a year down the side of the sofa? Some writers have likened his report to a new Marshall Plan, the project to rebuild Europe after the ravages of World War II. Except the funding required is double what was spent on that programme.

I’m sceptical of any meaningful action, but I can’t improve on Draghi’s own plea for action:

“For the first time since the Cold War, we must genuinely fear for our self-preservation. The reason for a unified response has never been so compelling…”

Until next time.

Graham